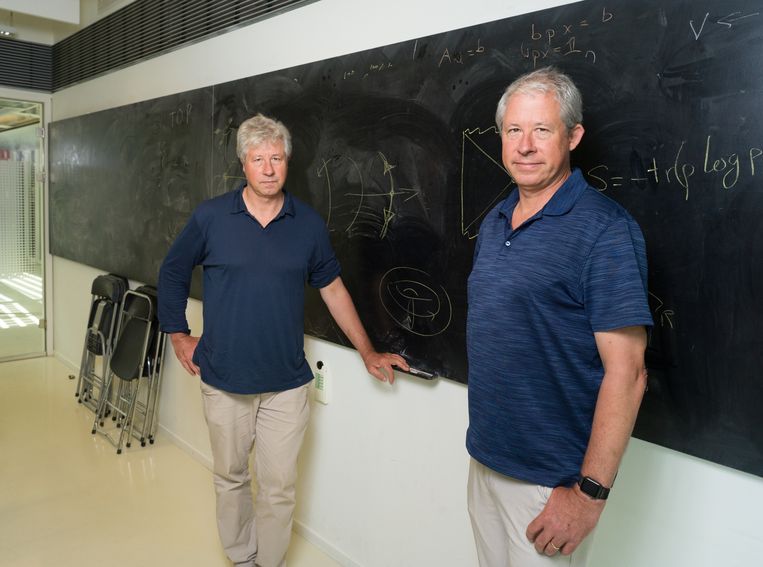

Twins Erik and Hermann Verlinde (60 years old) belong to the pinnacle of theoretical physics. Coincidentally, they were both in Amsterdam at the same time. Their field represents major breakthroughs. “This is still a very exciting time.”

We say “Hi Eric.” It turned out to be Herman.

A few minutes later, a second figure wearing blue-beige clothes appears in the central hall of the Science Park, Faculty of Science at the University of Amsterdam. They have the same white paper bread bag in their hands, and they both order a cappuccino. Then the two professors of theoretical physics try to reach the stairs, but the twenty-meter journey is difficult due to the constant interruptions; Lots of people talking to them.

Herman Verlinde is absolutely exceptional in Holland; He usually tours Princeton University in the United States. His brother Erik Verlinde has been at the UvA since 2003.

This year the twins turned 60 years old. They look back and study a photo of themselves from 1988, when they were 26 years old, before completing their PhD at Utrecht University. They were part of the research group of Gerardt Hooft, the famous theoretical physicist who later won the Nobel Prize. The brothers had already made a global name for themselves and were about to take off into the world.

Why did you stand out so much in the Netherlands?

“It was an exciting time for us,” Herman says. “There was no Internet. It took about three months before you really heard in the Netherlands what was happening on the other side of the ocean. This gave us the opportunity to develop our own line of research for a while. And that emerged. New ideas emerged, and it was clear that Eric and I We did it ourselves.”

The brothers were colleagues of Robert Dijkgraaf, the current Minister of Education, Culture and Science, who, like them, was a future major scientist. The three were called “The Three Musketeers” – and they were inseparable. Although they worked in ‘t Hooft’s group, the Knights much preferred to operate independently of any form of authority.

“Gerard Hooft was critical of string theory,” Eric says. “He didn’t really believe it, and he wasn’t alone. People sometimes wonder if it’s wise to work so hard on this topic. How long will it last? Who knows, maybe string theory will collapse and be ready in five years. People thought this was a risk.” ”

“But we felt there was something in it. We always felt that we had to follow our faith. And so it became very clear to the outside world that we did it independently of the moderators: our posts only contained our names.

Were you contradictory?

“Robert called us the Rebel Club,” Eric says. “The institute in Utrecht was quite traditional, but we were still moving in the direction of string theory.”

Hermann: “We basically wanted to forge our own identity. After a few weeks of being advised not to work on string theory, I decided not to listen to it. We learned from ‘t Hooft that we wanted to follow our own path. He was always a pioneer and a role model for us.”

In the third year of his doctoral research, ‘T Hooft traveled across the United States. And at the universities people used to say to him: “We would love to have those PhD students there.” On their return, T. Hooft advised the brothers to complete their doctoral research, and there was no point in staying another year.

Theoretical physics was still immature when she left for the United States. How have you seen the field grow?

Eric: “After we got our PhD, we were able to go to Princeton. There we immediately ended up in the Mecca Field. String theory had just gone through a revolution, and suddenly everyone started studying it. We were able to participate in that. But it’s not yet clear what If the field is able to fulfill all its promises. The great thing is that the field has already fulfilled many of its promises. Our vision of the relationship between quantum mechanics and gravity is now much further along.

Hermann: “The period after Princeton was also very special. After seven years we all returned to the Netherlands. Then, around 1995, everything started to fall into place. The field had matured thanks to the work done in the previous years. “Stephen Hawking and I have been working on black hole problems for a long time, and it turns out that there are answers to these questions. We organized the conference.”

He points to a poster on the wall. ‘’97’ chains she says. With a beautiful illustration: Amsterdam houses reflected in the rippling water, as if a pebble has just been thrown. Robert Dijkgraaf illustrated.

“For the first time, a conference on string theory was held not in the United States, but in Europe, with big names. We had a kind of informal style, where we would give a lecture in the morning and then devote a lot of time to discussion. Reception at West Indies House. Kopsticks was interviewed and featured in the newspaper. Stephen Hawking himself recorded, and it was welcomed. The theoretical physics group in Amsterdam has gained more insight. Now 25 years later, the conference is still held every two years in Europe. And this year in Vienna.”

You turned 60 this year, is it time to think about what you still want to achieve in science?

Hermann: “The great thing is that the steps that were taken in the 1990s suddenly became very important. We live in the information age, and thanks to the rules of physics, the world of ‘quantum information’ is now beginning to emerge. Many questions that have long been asked about black holes “It also has something to do with it. This is still a very exciting time.”

Eric: “The field has evolved tremendously, but the fundamental questions are still important. How should you think about black holes? About cosmology? I see a lot of developments, and I have great hope that I can contribute a lot to getting closer to the answer. In fact “The thing is, I think we’re once again on the verge of a new answer to the big questions about gravity – maybe within twenty or thirty years. I still want to try that.”

What is string theory?

String theory is a theory that attempts to integrate the four fundamental natural forces of physics (electromagnetism, the strong and weak nuclear forces, and gravity) into one comprehensive theory.

Robert Dijkgraaf, the current Minister of Education and Science, once described the theory as follows: “String theory is the most extreme form of theoretical physics and the most important candidate for a quantum mechanical description of gravity. This is necessary because current theories, especially Einstein’s theory of relativity, are incomplete. String theory doesn’t work with electrons or quarks, but rather with a kind of little rubber bands that can vibrate in all sorts of ways. Then all the different elementary particles around us would arise as vibrations of a single string, like the notes of a violin string. In this way, gravity can be described according to the laws of quantum mechanics. From this starting point, string theory can describe very heavy and very small objects, such as black holes and the universe immediately after the Big Bang.