via: Ties de packer

A special year

Breda – Jan Ingenhausz is Breda’s most famous unknown citizen. The man who made a groundbreaking discovery, was responsible for the health of emperors and was in contact with global players such as Benjamin Franklin. According to Judith Artmann of the Breda City Archives, the 18th-century physician and co-discoverer of photosynthesis has been unjustly forgotten.

“Why did he enter history with such importance?” Judith Artmann, a historical researcher at the Breda city archives, wondered this when she was researching Ingenhaus (he wrote Ingenhaus himself). It helped digitize the works of an 18th-century Breda physician contained in the city’s archives. “The more I read about him, the more interesting he became. He was versatile, and he had a Da Vinci-like profile. He’s a really cosmopolitan person if you look at what he immersed himself in.”

The city archives wanted to get to work by digitizing Ingenhaus’s works. Namely, to make his name better known to the general public of Breda. “The people of Breda probably know his name mainly from the Ingenhaus building which is located on Dr. Street. Jan Ingen Houszplein is located. But who is the man behind this name. It is now ‘History Month’, and its theme is: ‘Eureka!'” So scholars are put In the spotlight.It was the perfect time to release his works digitally and create a kind of snowball effect.

The text continues below the image.

Judith Artmann with a book in which Ingenhaus took notes – Tess de Backer

Childhood of Jan Ingenhaus

Ingenhaus (1730-1799) grew up the son of a pharmacist. His father, Arnoldus, ran the pharmacy from their home on Eindstraat Street in the city centre. Jan was a gifted boy and attended the Latin School in Breda. His talent for languages came in handy: “Arnoldus had once served in the army and fought in Scotland. His pharmacy was often visited by a customer called John Pringle, a Scottish army doctor. Their common ground created a bond, but there was a language barrier. That’s where Jan came in.” He acted as an interpreter between the two,” Artmann explains.

Study time

Inspired by his father and family friend Pringle, Jan wanted to study medicine. He did this in Leuven and Leiden. In Leiden he met someone who sparked a new interest in him: “Van Muschenbroek was studying at university and majoring in electricity. He developed the Leides bottle, a type of battery precursor. He inspired Ingenhaus with his interest and they kept each other informed about the experiments they were doing for a long time.

To England

After his studies, Ingenhaus returned to Breda. He ran a GP position there for ten years and left and never returned. “He wanted to follow his burning desire to expand his knowledge. He resigned his position as GP and went to London at the invitation of family friend Pringle. He was now a physician to the British court.

Pringle was also affiliated with the Royal Society. It is an association whose members included distinguished scientists, such as Isaac Newton (1643-1729), founding father Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), then Charles Darwin (1809-1882) and Albert Einstein (1879-1955). “Pringle introduced Ingenhaus to members of the Royal Society. He benefited greatly from this. In those days you only moved up the social ladder through mutual contacts and recommendations.”

Ingenhaus came to England with a plan. He wanted to learn all about smallpox vaccination. The smallpox epidemic claimed the lives of 400,000 people annually in Europe in the eighteenth century. England was one of the few countries to trial vaccination. “Ingenhaus began helping to vaccinate children through a contact he made at the Royal Society. He then helped vaccinate entire villages. Successfully.”

Work at the Vienna Court

This did not go unnoticed. Empress Maria Theresa of Austria lost three of her children to disease and barely survived herself. I contacted the British court because success stories from England had reached Austria. Pringle nominated Ingenhaus. He could not refuse and left for Vienna. There he succeeded in impregnating the Emperor’s relatives and was appointed court physician.

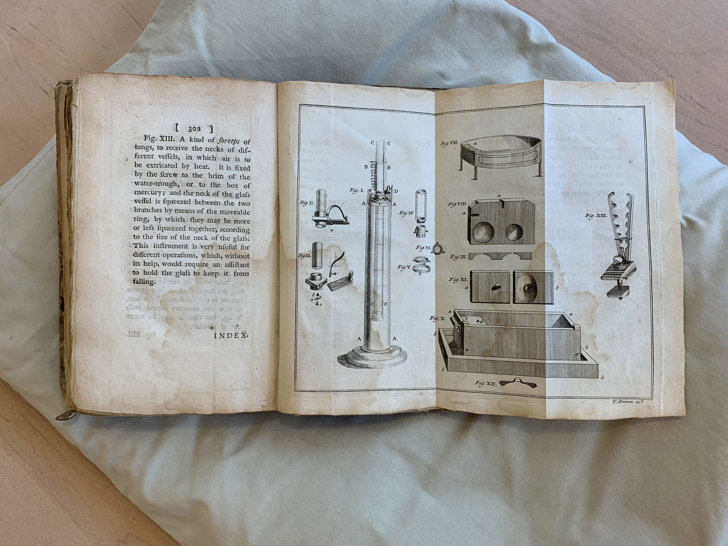

Ingenhaus earned a lot of money at the Vienna court, where he worked for eleven years. But he was looking for a challenge. He did a lot of research and experiments. It started with electricity, about which he corresponded extensively with Benjamin Franklin. Franklin eventually became one of the founding fathers of the United States. So he had real contact with the greatest on earth. He also conducted research on air quality, because theories emerged that air was not composed of a single substance for the first time. This led to the development of an air quality measure: the idiometer. He was also very interested in botany.

The text continues below the image.

Audiometer design – Tess de Backer

Finally free

But Ingenhaus did not fit into the strictures of life at court, where strict etiquette prevailed. So he left for England in 1778 and never returned to Austria. ”Go to the countryside and fully immerse yourself in experiences with gases, air quality and plants. After five hundred experiments, he made his most famous discovery: the process of photosynthesis. Of course, there were scientists before who were interested in purifying the air with plants. But Ingenhaus’s experiments showed that sunlight is essential in this process. This discovery was the pinnacle of his life.

Back to now

Why did he enter history with such importance? Looking back on Ingenhaus’s life, Artmann can answer this question for himself: “It was a time when science developed rapidly. Many inventors were not the only ones who discovered a topic. One started with the beginning, and talked about it with his scientist friends, while the other continued The other is to build on it. This is how things went in Ingenhaus’s life. Because one inventor is often unrecognizable, he is forgotten.

Ingenhaus must be rescued from oblivion this month. For this reason, the City Archives, in collaboration with the KOP Foundation, commissioned three artists to serve as inspiration for Ingenhaus’s works. They presented their designs on October 4 at the opening of the exhibition “The Most Famous (Unknown) Discovery of Breda!”. One of the designs should be given a place somewhere in the city. Artmann thinks this is a good start, but he believes there is more to be done: “I would call on all archives that store Ingenhaus items to digitize those works as well. The best thing is to have everything together in one place, but let’s start small. “I think we will be surprised by the discoveries that emerge.”

Devoted music ninja. Zombie practitioner. Pop culture aficionado. Webaholic. Communicator. Internet nerd. Certified alcohol maven. Tv buff.