A new study shows that developing countries face a huge gap in scientific research related to climate change, even though the communities and people most vulnerable to severe weather, rising sea levels and other dangerous effects of climate change, are limited.

Max Callaghan, the study’s lead author, said he’s a researcher at the Mercator Institute for Research on the Global Commons and Climate Change in Berlin.

“We know there’s a bit of a disparity in this global scientific system in terms of resources.”

The stark divide in the availability of scientific research is on the radar of climate experts, with significant hurdles for scientists in the South, such as access to prestigious (and expensive) scientific journals, lack of time and money to work on research, and even visa requirements that make it difficult for scientists to attend conferences and meetings. in the north of the world.

Experts warn that the division could leave developing countries without a way to decide where to focus climate mitigation and adaptation efforts to prepare for future weather disasters. Good climate science is also needed, as aid money from rich countries is targeted to help poor countries tackle climate change and spent on the right projects.

- Do you have questions about climate science, politics or politics? Email us: [email protected] Or join the comments now.

Machine learning mapping climate impacts

The new study, published this week in Nature Climate Change, used machine learning to examine more than 100,000 scientific papers around the world. The study aims to see if machine learning can aid the work of the United Nations Climate Science Organization, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, by facilitating manual examination of the thousands of papers scientists are currently studying.

The study authors divided the world into smaller grid cells and counted the number of climate studies looking at the effects of climate in those regions.

They found that far more climate studies of impacts have been published in developed countries than in developing countries.

For example, nearly 30,000 studies looked at areas in North America. 10,000 studies only looked at Africa, which has a population more than twice that of the population.

The researchers then used rainfall and temperature data to determine if a particular area was experiencing man-made climate change. They found that while three-quarters of Africans live in areas experiencing the effects of climate change, only 22 percent of them live in areas with a lot of scientific research on these effects.

This is a great interactive map of the study showing the strength of evidence on climate impacts by cell grid around the world. The darker shading shows more weight for the evidence. Filters can be used to select a climate drive and an impact class. Credit: Max Callahan.

Canada Funds Research in the South

A Canadian government agency is working to fill this research gap. The International Center for Research for Development, a federal crown institution, funds and encourages scientific research in the Global South with sites in countries such as Uruguay, Senegal, and India.

In 2019-2020, new projects totaling $166.4 million were funded by the International Development Research Center and associated donors. The center invites proposals for international development research that achieve specific goals, such as adaptation to climate change. Researchers and foundations can submit an application, with funds earmarked for local researchers or partnerships.

Although there have been many years of conceptual thinking about adaptation to climate change, we now need to implement these concepts here in Canada, and everywhere we see climate impacts, said Bruce Currie-Alder, head of the Climate Resilience Program at the Center for International Development. research. This is where microclimatology becomes very important, to know exactly how a particular area should adapt.

“It’s one thing to say that the world is getting warmer. There are certain parts that are drier and there are a certain frequency of storms,” he said.

“What does that mean in a particular region or country? This knowledge is absolutely necessary.”

Obstacles for African researchers

The stark dichotomy was highlighted in another climate science paper published in September and funded in part by the International Development Research Center (IDRC), which has investigated research funding in Africa. It found that 3.8 percent of global funding for climate change research is spent on Africa.

Even if that were the case, the money would mainly go to researchers from the North of the World. For example, 78 percent of that tiny amount of research funding in Africa went to institutions in Europe and North America. Only 14.5 percent went to African institutions.

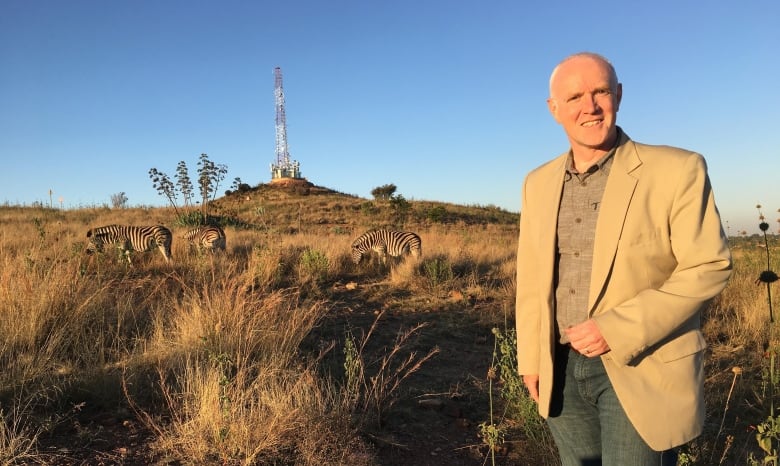

The solution lies not only in increasing funding for African researchers, but also in improving the quality of funding, said Christopher Tresos, a South African co-author of the research and senior researcher at the African Climate and Development Initiative in Cape Town.

“For example, increasing direct access and control over research, design, and resources for African partners when working with researchers from places like Canada or the United States, as opposed to externally set research agendas,” he said.

Trisos also noted that African researchers face obstacles even when trying to access published articles, many of which are on the Internet with paid walls that can exceed their budget.

“So publishing more open access data and more open scientific publications is a big part of the solution there as well,” he said.

These funding disparities lead to “unequal power dynamics in the way climate change research agendas in Africa are shaped by research institutions in Europe and the United States,” the paper said.

As a result, researchers in developed countries are setting research questions and goals for a global northern audience, rather than providing their local partners with actionable insights for using this research to combat climate change in Africa, the paper warns.

Original knowledge must be included

Michelle Lyon is a Senior Program Specialist in the International Development Research Center offices in Dakar, Senegal. He is currently working on a project funded by the International Development Research Center (IDRC) that studies migration in the region and how it relates to climatic and environmental changes on water resources and agricultural productivity.

Lyon welcomed the study of machine learning, but noted that the technological method he used represented the resource gap between North and South scientists around the world.

“There is a risk of some kind of new global divide, with the rapid and accelerating development of artificial intelligence and machine learning tools being developed in the North with Northern ideas, with Northern datasets and Northern bias,” he said.

It’s also important to consider who is considered an expert, Trissus says. He adds that there are many barriers to research beyond race and gender, which hold back some people and some forms of knowledge.

“Fortunately, the teams within organizations like the IPCC that started changing copyrights are becoming more diverse,” Trisos said.

“There is also a greater appreciation for not only scientific knowledge, but also indigenous knowledge and local knowledge, because it contains a valuable history of how people in places have been affected by climate change.”

Even without much research done in the South, it’s clear that climate change is affecting people.

“I think it tells us that even with this very small amount of funding and research efforts, there are still really strong indications of the serious impacts of climate change on people’s health, food security and biodiversity in Africa,” Trisos said.

“But we will know a lot more as more resources are devoted to this problem.”

Do you have questions about this story? We answer as much as possible in the comments.

Devoted music ninja. Zombie practitioner. Pop culture aficionado. Webaholic. Communicator. Internet nerd. Certified alcohol maven. Tv buff.